You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Firefly/Serenity

- Thread starter PhoenixVader

- Start date

Wicked cool! Most awesome project. I love this...

I assume you have a Livery, Apothocary, and a Mercantile. I tried to think of unusual names but shops like you would find on Little House on the Prairie.

Just thoughts.

Best,

DBCooper

There isn't a livery exactly, and it's a great idea. Lots of the local pubs have a place to tie up a horse, but there are plenty of unnamed buildings along the main strip of Ransom that could serve as a small, stabling areas.

As for an Apothocary, we have a massage/spa place and two separate health clinics (the Alliance medical clinic on the tarmac and the old Camp 96 hospital which has a local doctor and serves the veterans and citizens of Ransom, but a true apothocary might be nice too.

As for Merchantiles, we have the 'Folks Market'.

Another detail and the list of remaining places to be named...

EDIT: all major locations are named.

EDIT: all major locations are named.

Last edited:

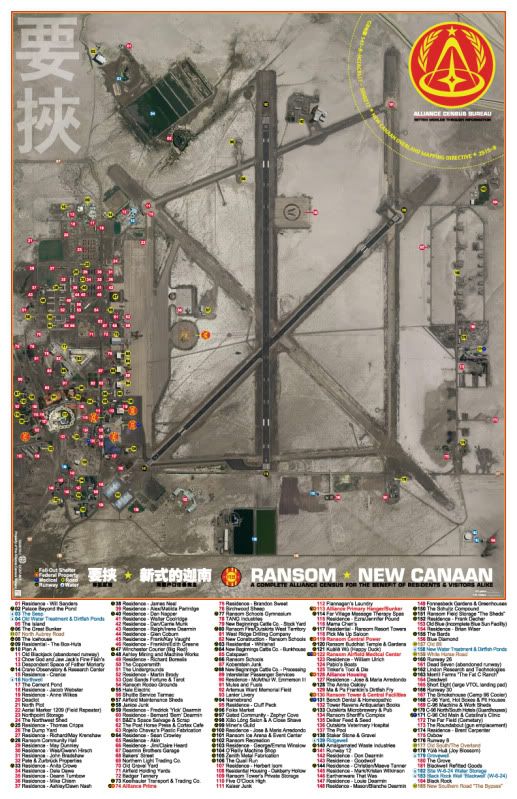

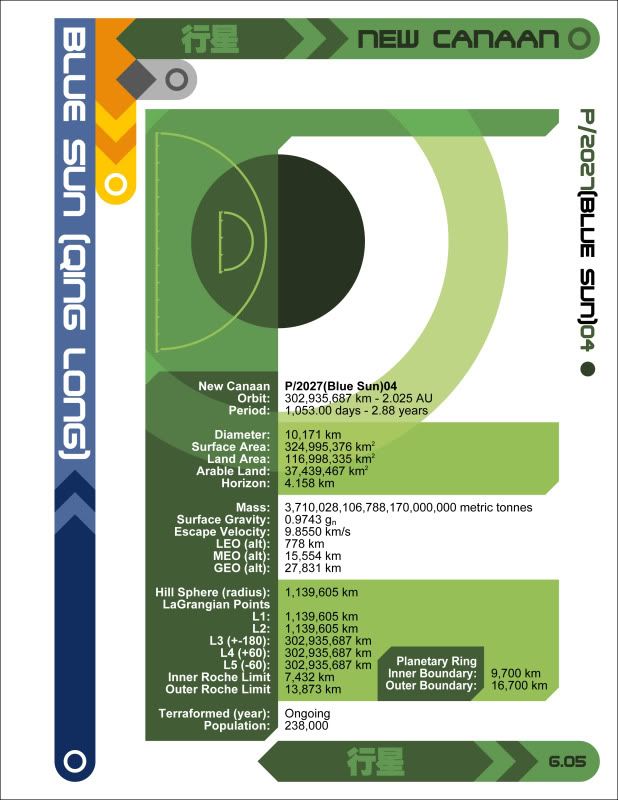

And a little information about New Canaan itself from The Verse in Numbers... http://pics.fireflyprops.net/TVIN-2.0.pdf

Mike J.

Master Member

Well, what're the main industries and / or exports?

Or did the town grow up around the spaceport?

Why is the spaceport in that location?

Any local natural resources?

Any farming?

... (You misspelled gun "emplacement") ...

And "Earthenware That Was"? That's a terrible pun :lol

Is there an 'XYZ' Guild hall / meeting place for your major industries?

A (Unification) Veterans' hall?

Any local monuments / parks / recreation areas?

Major & minor power sources / plants?

Local Alliance seat-of-power? City hall or Customs House or something?

Veterinarian?

-Mike J.

Or did the town grow up around the spaceport?

Why is the spaceport in that location?

Any local natural resources?

Any farming?

... (You misspelled gun "emplacement") ...

And "Earthenware That Was"? That's a terrible pun :lol

Is there an 'XYZ' Guild hall / meeting place for your major industries?

A (Unification) Veterans' hall?

Any local monuments / parks / recreation areas?

Major & minor power sources / plants?

Local Alliance seat-of-power? City hall or Customs House or something?

Veterinarian?

-Mike J.

Last edited:

Well, what're the main industries and / or exports?

Or did the town grow up around the spaceport?

The town produces scant exports, but there are exports. The locals produce and ship several locally grown plants, some fish, beef, and a mix of microbrewery goods, but the town lives on the import shipments of the airfield.

Why is the spaceport in that location?

Several wells were dug there and it became central to the communities that developed around it. The Alliance took it over and used it during the War.

Any local natural resources?

A deep, but sustained aquifer.

Any farming?

Yes. North and West of Ransom. Cattle and stock are also there and some mining South of Ransom.

... (You misspelled gun "emplacement") ...

Thanks you for catching that.

And "Earthenware That Was"? That's a terrible pun :lol

-Mike J.

Earthenware That Was - Thomas Grooms, Proprietor.

Thomas Grooms owns the best little salvage/stoneware business this side of...well...this side of anywhere. One has but to cross the handmade tile threshold of this archeological rummage repository to discover some of the finest trifles, tokens, trinkets and trophies ever discarded by humankind or fashioned by human hands. Baubles of bygone days are there for the buying, and on a good day, there for the stealing. Good deals on well used goods are just an everyday part of Earthenware That Was. Remembrances and relics line the walls, stalls and hallowed halls of this collectible crockery shop. If you're searching for that certain you-don't-know-what, then ETW is the place to find it. For the very best in stuff that was, and terra cotta that is, Thomas Grooms is your man.

This is an excerpt from Ransom's early history...

Ransom Notes: Part 1

by William Pace

The Verse is a wide and varied place, filled with hurtling planets of every hue and description. Each of them was carefully tailored to produce the highest potential for livability as citizens of the Core travelled out amongst the stars. While most of them presented few if any problems, New Canaan proved to be...stubborn. Like most of the planets that make up the Verse today, New Canaan started as something else, and struggled to remain just the way she was.

The first terraforming teams touched down on New Canaan in 2398 and began to alter her mass, tilt, spin and gravity almost at once. By the time the planet had reached her late compression stage she showed as much promise as her moons. By 2406 she had already been altered sufficiently to suit manned facilities and she was scheduled to begin true terra-forming alongside her nearest neighboring planet, Meridian. Atmospheric processors were brought and built on the planet and they began to alter the very air that same year. Even though terraforming had become a thing of every day life, it was made obvious very early on that New Canaan presented certain atmospheric and geological challenges. Simply put, she wouldn't give way to technology. While Meridian continued to change and evolve under the careful auspices of the governing powers at large, New Canaan refuses to yield herself to change. Still, despite numerous ongoing setbacks, the frontier scientists and pioneering laborers who came to call her home settled in and decided to make a go of it just the same.

After the first decade of atmospheric alteration the air became breathable in an 'adequate' or 'passable' way. Which is to say that scientists living billions of kilometers away and under ideal conditions gave the planet an acceptable review. People actually living and working on New Canaan took this recommendation with a grain of salt and kept their air masks on for another year or two. While it is true that the air was sufficient enough for life in the harshest sense, the atmosphere of the planet overall was harsher still, presenting storms of such magnitude as to make breathing seem like a secondary concern. Violent windstorms would sweep across the barren landscape frequently laying whole facilities to waste, and while the rain tasted not much different than it might on other planets, it wreaked havoc on instrumentation and machinery over time. Still, life continued.

By 2417 the planet was sufficiently stable in mass throughout that site surveys could be conducted for future development and settlement. Baal's location as a settlement hub was already well established just North of New Canaan's equator in what would become the greenbelt of the world. Survey teams had also found numerous favorable locations in the area called the Southshores, due mostly in part to the moderate climate and proximity to coastlines. While not the last, nor the furthest to be chosen, the Outskirts was often considered the least favorable of the sites chosen, but only because it bordered what could likely become one of New Canaan's high deserts and because it was so far from any of her oceans. Yet while the outcome of the Outskirts region was in question, it proved more geologically stable than any other site in New Canaan's development. Also, early tests showed large deposits of accessible, underground water.

It should be pointed out that names are often subject to change in developing regions of uncharted worlds. The Outskirts was not originally called by that name. The first designation for the area was Discovery Region 2-North, with additional numeric attachments, but the name was so quickly eclipsed by "Outskirts", that even the survey teams used the nickname more often than not. DR2-North was host to numerous surveys between 2415 and 2417. The place was scouted again and again by ground teams, survey drones and satellite imaging devices to find primary drilling sites. Sites within DR2-North were rated not only for ground water accessibility, but also for a well site's proximity to good soil. The areas in and around the region showed great potential for agricultural development, especially site W-6-24, which showed some of the greatest promise during early terraforming and was eventually chosen for one of the earliest drill sites for development.

Now, if you ask anyone from the Core where the Outskirts are, you're likely to get a strange look. Some people will direct you to the suburbs. Some will shrug. And others still will say, "Leave me alone you strange person, I have an appointment with a hammock by a bioluminescent lake and can't be bothered", and reasonably so. New Canaan is as far from the imaginations of most people in the Core as a day without running water. The same goes for a place like Site W-6-24. If you aren't from the immediate area, you couldn't possibly know where it is. In fact, many of the people who live quite close to the place now don't know the name, because it didn't last the test of time.

Early in the history of Site W-6-24 the name was changed to Black Rock by the workers of the Deep Creek Drilling Company, owing to the presence of a very black outcropping of stone in an otherwise flat landscape. For the teams sent to delve there, the place served as a shelter from the prevailing winds of the Outskirts and high ground for broadcast beacons. It was also excellent for watching the sunsets (which were particularly spectacular in the early days of terraforming and occasionally still are). The place also provided all of the water that it had promised in the surveys and the encampment thrived. The drill site was as remote as one could get on New Canaan, and still have someone to talk to, but that name didn't remain either. Not only did the name 'Black Rock' begin to gall some terraforming teams, what with the struggle to make New Canaan livable and it's connotations of failure, another name came along which eclipsed it altogether. While the rocky outcropping still bears the name today, as does the well there, the community which sprouted up from the irrigation of Black Rock Well came with a new name.

Ransom.

Like Site W-6-24 and Black Rock, most people have never heard of Ransom. It's a place of folklore and fiction to most, and a place of allegory and romance to all but a handful. There are many stories that have come out of Ransom over the years. It's the kind of place that lives or dies by these stories. The place is so far removed from everything, that it thrives on a healthy economy of tall tales, heroic misadventures and the local color that fuels the daily gossip. People import and export a continuous flow of anecdotes and narratives from the place. They trade in fables and dine on apologues. They pour myth over their breakfast serials. It's fitting then, even poetic, that Ransom herself should be named for a story which came before. Long before.

During the distant, dark crossing from Earth That Was to the Verse That Is, a very dog-eared paperback was passed around the electric blue campfires of more than a few huddled refugees. This sci-fi western was shared around among the new pioneers as they travelled the great expanse aboard one of many far flung generation ships. From person to person it traveled, lovingly read, dropped, torn, taped, bent, mended, and weathered in every possible way that a few hundred hands might erode a book. Its withered pulp was well loved by all, not because it was remarkable in its imagery or possessed of clever characters. It was simply one of only a few real, tangible books to sail aboard the generation ship Silver Island. Eventually it was even transcribed into an amateur theatrical piece that was well received by all aboard, and while the original book itself fell apart well before Silver Island reached the Verse, some well preserved pages remained and the story still lingered on.

That book was called Ransom of Blood.

Now the small town of Ransom, as described in that unique novel, was a lonely, shanty town as dusty and removed from civilization as any iconic spaghetti western hamlet could have been. The same could be said of the first tent encampment at Black Rock, where the sunburnt drill jockeys of the Outskirts delved deep to bring water up to the thirsty plains of New Canaan. So similar were these two places, the imagined town of an Earth almost forgotten and the waking haven in the barren Outskirts, that it seemed only right and proper to christen the place Ransom. Of course it didn't hurt that one of the rig captains working for Western Drilling (which had taken over from Deep Creek Drilling by 2439) knew the story well enough to tell it over and over to pass the time there.

And so Ransom was born, conceived of two great parents. Work and water.

Work was the first to reach the Outskirts of New Canaan, arriving in the form of struggling settlers, outbound from the hustle and bustle of the pregnant Core. They came with little more than they could carry or haul. These were the new vagabonds. The Core's outcasts bent for a life they could call their own. Prospectors and planters. Homesteaders and haberdashers. Men and women with an eye for what could be with just a little sweat and determination.

Then came water. Water was the mother of Ransom and every other town in the Outskirts. Water made a life worth living, and no living could be made without it. Why without water, no township or community could be carved from the harsh, unfriendly reaches of the Outskirts in the early days. New Canaan had too recently begun terra-forming then to be a garden, tilled or not. If you had water, you considered yourself lucky and guarded wells in ways that only desert prophets would understand.

Yes, Ransom was just one more place where a weathered weed of an immigrant could chase down a hard day's work with a gritty glass of h2o. Nevermind the taste.

Just like Nineveh of the Southshores and the ever growing Baal, Ransom's early days were consumed with tilling and construction. The need for food, water and shelter were not lost on New Canaan's first inhabitants and they dug in like ticks. Shipping containers became shelters and shelters became homes. The desert blossomed, and while much of it was thorns and thistles, the Ransomites thrived.

The first well was completed in the late Fall of 2439. The water was used as much to wet the soil as it was to cool homes in summer and refrigerate the meat and food stocks of the early settlement. Within half a year there were three working wells at Ransom, so that seeds were sewn late in the fall of 2440 with the hopes that they would cultivate under an insulation of snow against the coming year. As winter gave over to warmer days in the Spring of 2441 there was water enough so that even the poorest settler could look past everything that Ransom wasn't. While the fields weren't lush, they were alive. While cattle in great numbers wouldn't come until much later, sheep and goats thrived. While the conveniences of the Core were far removed, so were the laws that overburdened the free. Ransom had taken root and would outlast as many as seventeen early communities spread all over the Outskirts of New Canaan.

Within the first few years of settling the Outskirts, six neighboring communities had all but failed, including New Delker, Burner, Alder Flats, Swales, Birchwood and Poeville. The winter of 2441 had been a long one, and it proved very hard on folks, as did the three winters afterward. The temperatures of that winter were the lowest on record for New Canaan. The settlement period between 2439 and 2441 had positioned more than 37 different settlements in the Outskirts, and they were simply spread too thin and too wide to handle a hard season, hot or cold. Ransom, being central to so many of these attempted townships, and being possessed of the only true airfield and fuel station of the region, grew with every failure that winter. Each time the temperatures plummeted, people would retreat to Ransom, so the town would absorb 10 families here and twenty families there. Every time a weatherworn battalion of settlers was pushed off the front lines by a cold and unyielding front, Ransom got a little bit bigger and a little bit stronger. When the spring of 2442 finally showed at the end of that dark tunnel, Ransom had almost tripled in size and had gleaned the hardiest settlers of every failed experiment in the Outskirts.

As the weather warmed, some dauntless pilgrims returned to the ruin of their homes. Some of them stayed in Ransom and made a go of it through three more, back to back winters that made each previous year pale by comparison. The community of Burner rebuilt three times, but quit the place the forth time around. Swales remained dead almost two full decades, to be resurrected later by a former prisoner of camp 96 just after the Unification War. When he learned that Swales was just a fancy name for a moist, marshy trough, he would forever refer to the place as göttlicher abzugsgraben. The Divine Ditch. Alder Flats would eventually become part of the spreading Westcastle Ranch, but the original name would live only in memory. Birchwood would become a sheep camp during warmer months and Poeville would play host to two mining companies only to live, die, live and die again before abandonment in 2444. New Delker became a ghost town after it's first winter, but a sign which hung over New Delker Hall still hangs in Big Red. The sign reads 'Welcome to New Delker. We're here for the duration.'

All the other towns of Outskirts survived the 'Four Winters' (as they were called ever after) through a combination of regulated hibernation or migration to Ransom during the winter months. Those communities closest to Ransom had the choice of toughing out the cold while maintaining the only localized commerce or packing it all in and facing the harsh environment fueled by pure will. Those were the defining years of the Outskirts. Those were the years that sifted the weak from the strong, creating the hard, pragmatic and undaunted people that would make the Outskirts as romantic and unrelenting as the Outback had once been on a fading Earth. If you survived the Four Winters and the later Windstorm of '59 you were there to stay and no one would ever say different.

One of the earliest immigrants to put down roots on New Canaan was Artemus Ward who financed the construction of Big Red, the largest hanger at Ransom airfield. Artemus was a not a rich man as wealth went in those days, but every early idea of his had proven so worthwhile in the long run, that he could often get people to back his endeavors whenever there was a shortfall and the airfield at Ransom was no exception. The idea of a large scale landing field to accommodate both old, new and Rim built boats had already proved favorable to Ransom during the Four Winters, so many a budding businessman and sodbuster chipped in to expand the potential of the town. Artemus even managed to fund a few of the projects through more official channels, drawing on the loose laws surrounding mining exploration grants. Equipment purchased to explore heavy and precious metals could be used throughout the year to build facilities on Ransom's front lawn. With a labor force at a premium, but a shortage of jobs, Artemus was able to exploit opportunity to the fullest. He built the town with every single piece of credit or coin that he could scrape together and kept many a family in food and clothing while doing it.

These were the meat and potato days, and no one was sure that they would last, but it inspired more than a few bored, bright, visionary scientists and engineers to pull up their Central Planet roots and replant on the Rim's questionable soil. Old men who had begun to look out their windows at departing ships bound for places elsewhere quit their comfortable situations for pastures less green, but all the more inviting. Young men, fresh from furrowed fields or newly accredited by colleges, hitchhiked to the furthest reaches of the Verse, anxious to see the new Frontier. Ransom welcomed them all. Despite the hardships of a planet still under the terraforming umbrella, Ransom and other cities across New Canaan were thriving, in a kind of colonist expansion effort that had gone beyond a few restless nomads. Maps were forming now. Atlases of substance were being created and catalogued and the chronicles of Canaanites everywhere were echoing out to the Core.

By 2445 the airfield had grown to accommodate both vertical and horizontal landings and takeoffs. There were nearly five large hangers and the housing west of the airfield had grown enough to attract bigger business. Whitehall Corporation, Tiān-Cháo and Parker-Morris had not yet been absorbed by Blue Sun, and each of them added to the infrastructure of Ransom by supplying raw and prefab goods. Ransom also saw the arrival of the first, true Rim-runners, the fly-by-night pilot/captains willing to fly even the most questionable of airframes between the Core and the sticks. Free market and black market were almost one in the same in those days as everyone sought to stake a claim on New Canaan, and as the planet benefitted, so did Ransom.

Life in Ransom became more settled then and the period from 2446 to 2464 saw great local growth. The people of the Outskirts had found their stride and babies were being born. With the New Canaan Settlements Bureau's declaration to open the Outskirts for mass homesteading in 2447, life there thrived even further. Children could now be seen playing on lawns of scrub grass and climbing on playgrounds made from old machinery and discarded tires. The vitality of the place could now be measured in her community dances, public auctions and local races. Friendships were well formed and reputations well established. Schools for every age were created and stores were selling the new in place of the old.

Shortly after this period of great growth, Artemus Ward died. The Yellow Creek Mine out of Nixon was all but destroyed in a fuel explosion on March 2, 2467, killing 14 people and injuring 26. While Artemus Ward was not killed during the explosion, he died within days of the incident. During an attempt to rescue survivors from the mine's main air shaft, Artemus Ward lost his footing and fell from a height, sustaining multiple injuries. While he fell no more than ten feet to the ground, Artemus was still badly injured. Blood clots stemming from his injuries caused a pulmonary embolism and he was pronounced dead on March 6, 2467. Of course, all of Ransom mourned. The service held at Ransom airfield was the largest single funeral in Ransom's history, before or since. Over 2,000 people attended the ceremony, and some two dozen speakers were heard. Artemus Ward was lauded by all and he was described as everything from city father to historic visionary. In the end, it was his friend Cole Benson that described him best when he said, "If you want to be twice the person you can be, then just be half as good as Artemus Ward was." Ward's last will and testament left everything to the community with a special note that no debts owed him or to his progeny should outlive him.

With the death of Ransom's greatest patron, a vacuum formed. Many people stepped up to fill the void, and it took more than a few to try, but everything Artemis had set in motion went forward. By 2471 most of the present day airfield was complete. By this time a tower and some seven hangers existed at Ransom. A water treatment plant was in development North of town and housing had doubled again for the first time since the boom following the Four Winters. Ransom could now boast several favorable watering holes, eating establishments and at least two full time hotels. Grain was being shipped to Ransom and beyond. The first real cattle development was on the start in the surrounding hills and goats were thriving better than ever. Postcard pretty it wasn't, but well over 3,000 people were living and working there with a fluctuation in population of up to 500 persons on any given day.

By 2482 trades were passing to the third and in some cases fourth and fifth generations of the Outskirts. Pacific Trans was well established by 2483 and enough goods came and went from there that memos about it appeared on the desks of Amalgamated Waste industries and the Trader's Guild. Then Ransom saw its first decline in population since its inception in 2486. Efforts were made to expand the airfield, which had fallen into disrepair over the years, but a new airstrip wasn't constructed until New Canaan's centennial milestone in 2498, which encouraged a high price tag construction boom for almost eight years. 2500 saw the highest population mark ever seen in the Outskirts, with Ransom boasting over 6,000 residents, but the population had climbed to over 7,000 by 2506 as Canaanites continued to sew and reap the rewards of a life unhindered by the Verse at large. While it couldn't be called cosmopolitan, it was life and people wanted for little.

Then came the War.

Mike J.

Master Member

*****. That's a lot of writing.

Which one's the foundation? Is the map based on the story, or is the story based on the map?

Have you gone through the story / map and checked that every mentioned / named major place exists in the other?

Also - one that just occurred to me - is there a clinic / doctor / hospital?

-MJ

Which one's the foundation? Is the map based on the story, or is the story based on the map?

Have you gone through the story / map and checked that every mentioned / named major place exists in the other?

Also - one that just occurred to me - is there a clinic / doctor / hospital?

-MJ

Is there an 'XYZ' Guild hall / meeting place for your major industries?

Yes. They meet in many capacities and at different places. Ransom is one of the few places in the Verse where Unification really works. Former prisoners and guards of Camp 96 live at Ransom. Retired officers, pilots, soldiers and the like all share the town. Despite the strong Alliance presence in the form of the tower, dome and clinic, most local disputes fall to the Ransom Sheriff's Office under the control of former Independent Captain, Christian Tanner.

Their is a community center and a municipal center. They are both used for meeting public, private and professional.

A (Unification) Veterans' hall?

Camp 96 still has regular events for both sides to celebrate separately and together.

Any local monuments / parks / recreation areas?

The Ice Arena, Recreation Center, Community Hall, and playing fields.

Major & minor power sources / plants?

There are redundant facilities in and outside of town. Some of them are antiquated. Some are new. The Alliance facilities have dedicated power supplies, generators and batteries, and most buildings built at Ransom in the last 10 years have 'bunkers' with small scale power sources.

Local Alliance seat-of-power? City hall or Customs House or something?

The Alliance Main facility serves as the 'seat of power', but as I stated, the power is very unified and easy going. It's a pragmatic place.

Veterinarian?

Yep, but I haven't listed one yet.

*****. That's a lot of writing.

Which one's the foundation? Is the map based on the story, or is the story based on the map?

The story is the foundation, but as the two have evolved, some of the map has changed it. I was using Ransom as an idea for writing and gaming long before I made the map. Each unique place that I've named personally stems from a story or idea.

The map was pieced from dozens of images.

Have you gone through the story / map and checked that every mentioned / named major place exists in the other?

Yes. The story and map have become a tandem project.

Also - one that just occurred to me - is there a clinic / doctor / hospital?

There is an emergency, fully staffed medical facility right on the airfield under the control of the Alliance. It is staffed by many offworld doctors and residents.

The Camp 96 'Old Main' is now a clinic under the direction of Doctor Catalina.

Mike J.

Master Member

Well, if you're looking to fill a slot, I'd suggest a humble town newspaper - or broadwave ... sheet ... or ebook, or whatever the hell they'd call it.

Founded upon the terrible pun, "The Ransom Notes." Too obvious?

I supposed that it would have to be rather rarely published - maybe once a week? Mostly lists of major commercial ships coming and going, and what little local / planetary news there is. "Meet the new vice-advisor for The Tower and Dome! Born in CITYNAME, PLANETNAME, John Smith is a career civil servant who's last posting was a five-year stint in CITYNAME, PLANETNAME ... Let's show him a warm, Ransom welcome!"

The electronic newspaper publisher can also double as the physical print shop for ... large-sized printed items and large-number print runs. Banners, large posters, large signs, a lot of blank forms - the kind of stuff that wouldn't be feasible or economical to DIY.

-MJ

Founded upon the terrible pun, "The Ransom Notes." Too obvious?

I supposed that it would have to be rather rarely published - maybe once a week? Mostly lists of major commercial ships coming and going, and what little local / planetary news there is. "Meet the new vice-advisor for The Tower and Dome! Born in CITYNAME, PLANETNAME, John Smith is a career civil servant who's last posting was a five-year stint in CITYNAME, PLANETNAME ... Let's show him a warm, Ransom welcome!"

The electronic newspaper publisher can also double as the physical print shop for ... large-sized printed items and large-number print runs. Banners, large posters, large signs, a lot of blank forms - the kind of stuff that wouldn't be feasible or economical to DIY.

-MJ

Well, if you're looking to fill a slot, I'd suggest a humble town newspaper - or broadwave ... sheet ... or ebook, or whatever the hell they'd call it.

Founded upon the terrible pun, "The Ransom Notes." Too obvious?

I supposed that it would have to be rather rarely published - maybe once a week? Mostly lists of major commercial ships coming and going, and what little local / planetary news there is. "Meet the new vice-advisor for The Tower and Dome! Born in CITYNAME, PLANETNAME, John Smith is a career civil servant who's last posting was a five-year stint in CITYNAME, PLANETNAME ... Let's show him a warm, Ransom welcome!"

The electronic newspaper publisher can also double as the physical print shop for ... large-sized printed items and large-number print runs. Banners, large posters, large signs, a lot of blank forms - the kind of stuff that wouldn't be feasible or economical to DIY.

-MJ

Ransom Notes is the title of a piece being published about the project, so I'll have to think about the name.

I love the idea of a newspaper/print shop. There are some 16 small settlements that get their news and information out of Ransom, to say nothing of the many, many, many social events. There ain't much to do, so a print shop could make a comfortable living.

Mike J.

Master Member

You can tweak whatever you want to - I'm just tossing an idea out there.

Are the various large corporations represented in town? Pacific Trans, the drilling companies, the mining companies? Major freight companies?

Even if site XYZ was abandoned, they might keep a small office there, for assaying, trading or surveying purposes.

Is there a connecting ground transport ... route to and from town? A rail line or rough road or cow path, or something?

-Mike

Are the various large corporations represented in town? Pacific Trans, the drilling companies, the mining companies? Major freight companies?

Even if site XYZ was abandoned, they might keep a small office there, for assaying, trading or surveying purposes.

Is there a connecting ground transport ... route to and from town? A rail line or rough road or cow path, or something?

-Mike

You can tweak whatever you want to - I'm just tossing an idea out there.

Are the various large corporations represented in town? Pacific Trans, the drilling companies, the mining companies? Major freight companies?

Even if site XYZ was abandoned, they might keep a small office there, for assaying, trading or surveying purposes.

Pacific Trans ships to and from Ransom, but handles their operations through a second party. TANG industries houses their most remote connection at Ransom through representation at Keelhauler's office. The well drilling companies have come and gone, but they still have a presence at Baal, the world capitol. There are well drillers at Ransom, but not on the industrial scale of the former settlement projects. To understand the shipping in the Ransom area, one has but to read the following memo, which I wrote up over a year ago.

"I've written up a few materials about Blue Sun's limited presence at Ransom on New Canaan. There is a large, unfinished distribution center there, some old warehouses (now rented out to other supply companies) and a small sales office at the airfield. The site is operated by only two employees of Blue Sun, Wilson 'Dusty' Carver and Max Standish.

The memo below explains some of the backstory for Blue Sun's 2212 Facility.

Blue Sun Supply Depot: 2212 at Ransom

Status: In Review

Internal Memo 32316: Committee for Reviews - Level 2 Priority

To the Committee of Operations,

The status of our supply depot at Ransom on New Canaan has come into question once again, what with the surprising lack of interest in consumable goods in bulk quantities and an unexpected volume of localized imports and exports. As you know, it was first assumed that Ransom would be the ideal place for high volume, long term storage of goods, due to the community's size and relative planetary isolation, the presence of an airfield and the close proximity to smaller neighboring towns and settlements. The initial studies of Ransom showed that the location was ideal for ground floor consideration and that there was every indication that a facility equal in size to Blue Sun's holdings at Dacy, Bella Union and French Creek on Deadwood would thrive in the Outskirts. Not so.

After an in depth study of competing corporations in the Blue Sun System, such as Corpus Christi, Tang and Ursa Major, it was shown that none of these competitors exhibited a vested interest in establishing a foothold at New Canaan. The combination of low population growth, delays in terra-forming stabilization and the lack of significant political and economical infrastructure nullified any and all high stakes competition. In view of growth estimations for post-war New Canaan, and with Blue Sun poised to set and control the local market value and distribution of goods, it was concluded that a depot would thrive at Ransom.

Armed with this information, ground breaking began at three separate locations starting with two large pre-fab warehouses. Blue Sun's 2212 storage facility was built in close proximity to the Ransom airfield and adjacent to the primary Alliance properties of the same. This location afforded Blue Sun both protection and ideal real estate. Within three weeks, foundations for a distribution center and office space had been added nearby. Site 2212 was completed and fully stocked in less than two months and it was partially staffed for the sale and marketing of goods. Trade with White Horse, Benson, and other neighboring settlements ensued, but far below expected estimates. Even sales at Ransom proper proved poor at best.

Within six years of service, Blue Sun's 2212 facility had garnished so little use that it was scheduled for liquidation not once, but four times. Sales were so poor, that construction on the distribution center East of the warehouse site was halted altogether. This memo constitutes the fifth and final review of site 2212.

Early information and studies of Ransom failed to take into account the many individual supply boats, sutlers and smugglers coming and going from Ransom. The traffic of small vessels through the airfield there was never considered when examining competition in trade goods. It was assumed that even a steady traffic of light and mid-bulk transports could never yield enough imports to constitute competition, but in and outgoing ships were selling more Blue Sun goods than Blue Sun itself. Add the unexpected volume of cattle interests and the presence of other small livestock ventures and Blue Sun was further undermined. Even the sales of alcohol and ammunition, generally considered a cash cow for corporations on the Rim, were eclipsed by local breweries out of Ransom and New Cumberland, and local shops were regularly stocked with small arms and munitions.

Despite causes or reasons of failure, site 2212 has proven unprofitable in short and long term reviews. After much consideration, and considerable hindsight, it is recommended that site 2212 be sold at cost and that the goods therein should be liquidated and/or moved to Blue Sun holdings at Baal and Bishop Docks. In the opinion of this office, Ransom's status as a corporate commodity should be reduced in priority from a supply hub to a remote sales point. This office can only recommend the maintenance of the smaller sales office building and property sheds at the same location. All other facilities should be sold or rented until the financial climate at Ransom should show marked improvement in Blue Sun's favor.

Respectfully,

Edward James Clawson

Accounting, Requisitions and Reviews

Clawson and Peels

CCC-2341-6767-22-900"

Is there a connecting ground transport ... route to and from town? A rail line or rough road or cow path, or something?

-Mike

There is no 'train' to speak of to and from Ransom. Ransom is way out there in terms of location relative to other major population zones on New Canaan. However, the Quail Run*, Number 6, Winchester Courier, Keelhaluer and Intersteller Passenger Services all operate local passenger traffic in and out of the area.

There are also groomed, paved, and dirt roads leading to other communities from Ransom, including the Overland, which is little more than a general path to New Cumberland, Eastward.

*A further note about the Quail Run...

"Quail Run

There are many hangers and airdocks at Ransom Field. Most of them look the same. It's a modest place where pilots foreign and domestic rest their heels when they're not gallivanting about the Verse. One of the local regulars at Ransom Field is Preston Whitingford and he owns the Quail Run. Now the Quail Run is a kind of fly by night courier and taxi business, perfect for the daring businessman and traveler. While transport and package services are common enough about the Outskirts, there is nothing common about the Quail Run or it's owner/operator.

First, theres the fact that the business sports two of only a handful of surviving Quails in the Verse. Second, no one in their right mind would fly one of them unless they had to.

This leads us to the subject of Preston Whitingford himself. You see, Preston was a Quail pilot during the War, which as most people know, is enough to set you apart from just about every other pilot in the Verse. Hell, it's enough to set you apart from most human beings. People who fly Quails are about as reckless, fearless or just plain dumb as they come. Most Quail pilots died flying them in the War, and not a few perished afterwards, but not because they died crashing the first or the second time. Quail pilots just kept going up, as dauntless as the fated dead.

So what sets Preston apart from any other Quail pilot? Preston crashed seventeen times.

Now most human beings would have walked away after the third crash. The hardiest of Quail jockeys might have held out for four or five healthy rendezvous with gravity. Not Preston. What any other person would have taken for a string of really loud wake up calls, Preston took as a sign from God.

When he crashed the first Quail in basic and came away without a scratch, that was God. When he was shot down over Walling at the Battle of the Range only to go up and get shot down again the same day, that was God too. Certainly the Almighty was with him at Sturges, when he downed a burning Quail in a crowded street plaza and took out the lobby of local hotel. It's hard to argue that the Creator of all held Preston in his hands when he put a Quail with one engine on the roof of St. Anne Hospital. Preston piloted more Quails to their doom than any other pilot of any kind, including his last flight of the war. On that day he crashed into an Alliance C-15 Yǔ Yǐng Qū, not because he was trying to destroy it, but because he needed to put the Quail down fast and the cruiser was the nearest place to land. He spent the next five weeks in a hospital bed at Elson Prison praising God amidst a hailstorm of surgeries, medication and not a little interrogation.

It follows then that Preston is a fan of the Quail. It follows also that he'll be a Quail pilot all of his unnatural days. If anyone ever needed a 'God is my copilot' bumper sticker, it's Preston Whitingford."

taimdala

New Member

Re: Map from Serenity

Hi, Moffeaton--Yellowjacket over at fireflyprops.net put me onto this thread and I gotta say, wow! So much shiny! But the link above seems to not work anymore. I got a 404/Not found error message. Has the picture of the map been taken down? I know I'm late to the party, but is there a way to see the map? Pretty please?

This was one of the maps seen (or not? lol) in Mal's room, from the film production.

It's the largest I have of this particular map...

http://www.roboterkampf.com/paperprops/Galaxy3.jpg

Hi, Moffeaton--Yellowjacket over at fireflyprops.net put me onto this thread and I gotta say, wow! So much shiny! But the link above seems to not work anymore. I got a 404/Not found error message. Has the picture of the map been taken down? I know I'm late to the party, but is there a way to see the map? Pretty please?

taimdala

New Member

Hello--just found the place, pointed to the forum by Yellowjacket over at fireflyprops.net. I was a big fan of propcircle.com and saved many of the publically offered pics before the site went down. I think I know who did the BS cigarettes in reply #20 in this thread, since it matches one of my saved pics:

blubeetle3, and it was posted at propcircle back in the day.

blubeetle3, and it was posted at propcircle back in the day.

Mike J.

Master Member

Very nice.

Does the color-coding in the key text mean something? I notice that some of the numbers are different colors, as is some of the text. I see the little symbols are explained, but are the text colors?

This may be slightly off-topic, but did you hear about those odd earthworks in the Chinese desert?

Might make for some interesting 'filler' for blank areas on the map - if you think you need any.

Mike J.

Does the color-coding in the key text mean something? I notice that some of the numbers are different colors, as is some of the text. I see the little symbols are explained, but are the text colors?

This may be slightly off-topic, but did you hear about those odd earthworks in the Chinese desert?

Might make for some interesting 'filler' for blank areas on the map - if you think you need any.

Mike J.

Very nice.

Does the color-coding in the key text mean something? I notice that some of the numbers are different colors, as is some of the text. I see the little symbols are explained, but are the text colors?

Mike J.

I made them different to counterpoint the fact that some are 'water' sources, some are with or without bomb (now Reaver) shelters. It made more sense when I first did them. Maybe I should just make them all black.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 3

- Views

- 482

- Replies

- 312

- Views

- 50,787

- Replies

- 367

- Views

- 53,940

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 30,567