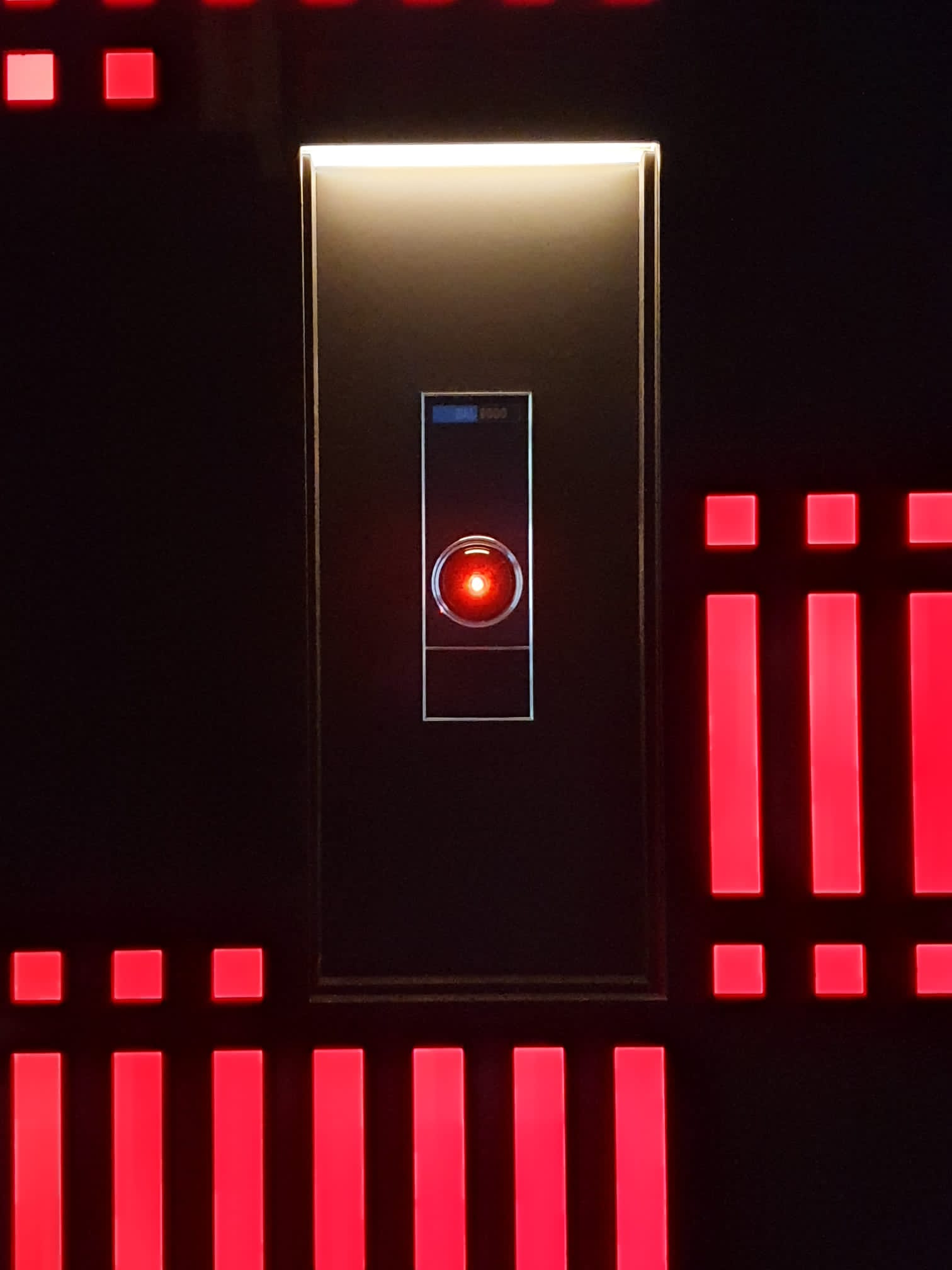

I’m sorry, Dave.

Some of you may have seen the load of research I did on the HAL 9000 camera faceplate prop from Stanley Kubrick's 2001: a Space Odyssey. I wanted to nail down what we know for certain about this truly iconic prop, and what areas remain a mystery.

HAL 9000's faceplates - everything you never wanted to know.

I also lamented that, although there have been countless replicas - commercial and amateur - of this famous design, nobody has really got it right, despite its modernist simplicity.

Recently I was given the opportunity to put my money where my mouth is, and build an actual replica of the prop for the travelling Kubrick Exhibition - soon to make its next stop in Madrid. And, well, that was too exciting an opportunity to pass up! It took a lot of pain and money, and some challenges working with a number of machinists, but now I think I can say that I've built the most screen-accurate replica of HAL yet made.

Four sources of information made this grand claim possible. First, the discovery of the actual lens model used in the movie - a Nikkor 8mm f/8 fisheye - by Amadeus Prokopiak and others was the Rosetta Stone. Second, the 4K Blu-ray release of the movie gave us high-resolution images from the actual film at long last. Third, Adam Johnson's publication of Frederick Ordway's production blueprint verified the key dimensions of the faceplate, at least from the front. And finally Karl Tate's research, that yielded two commercial prop replicas, was invaluable.

So there we go. But is it perfect? Well, no. There are a number of minor drawbacks and limitations to my model for the usual reasons - time and money. But I think it’s still pretty good. And the team in Spain did a lovely job of installing it in their “brain room” in Madrid.

The show opens on 21 December in the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid, Spain.

Exhibition Tour – Stanley Kubrick

STANLEY KUBRICK. The Exhibition - Círculo de Bellas Artes

Photo by Tim Heptner.

Some of you may have seen the load of research I did on the HAL 9000 camera faceplate prop from Stanley Kubrick's 2001: a Space Odyssey. I wanted to nail down what we know for certain about this truly iconic prop, and what areas remain a mystery.

HAL 9000's faceplates - everything you never wanted to know.

I also lamented that, although there have been countless replicas - commercial and amateur - of this famous design, nobody has really got it right, despite its modernist simplicity.

Recently I was given the opportunity to put my money where my mouth is, and build an actual replica of the prop for the travelling Kubrick Exhibition - soon to make its next stop in Madrid. And, well, that was too exciting an opportunity to pass up! It took a lot of pain and money, and some challenges working with a number of machinists, but now I think I can say that I've built the most screen-accurate replica of HAL yet made.

Four sources of information made this grand claim possible. First, the discovery of the actual lens model used in the movie - a Nikkor 8mm f/8 fisheye - by Amadeus Prokopiak and others was the Rosetta Stone. Second, the 4K Blu-ray release of the movie gave us high-resolution images from the actual film at long last. Third, Adam Johnson's publication of Frederick Ordway's production blueprint verified the key dimensions of the faceplate, at least from the front. And finally Karl Tate's research, that yielded two commercial prop replicas, was invaluable.

So there we go. But is it perfect? Well, no. There are a number of minor drawbacks and limitations to my model for the usual reasons - time and money. But I think it’s still pretty good. And the team in Spain did a lovely job of installing it in their “brain room” in Madrid.

The show opens on 21 December in the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid, Spain.

Exhibition Tour – Stanley Kubrick

STANLEY KUBRICK. The Exhibition - Círculo de Bellas Artes

Photo by Tim Heptner.

Last edited: