Prop Store

Forum Sponsor

This is Part 1 of a 5 Part Series. Be sure to catch all 5 parts!

---

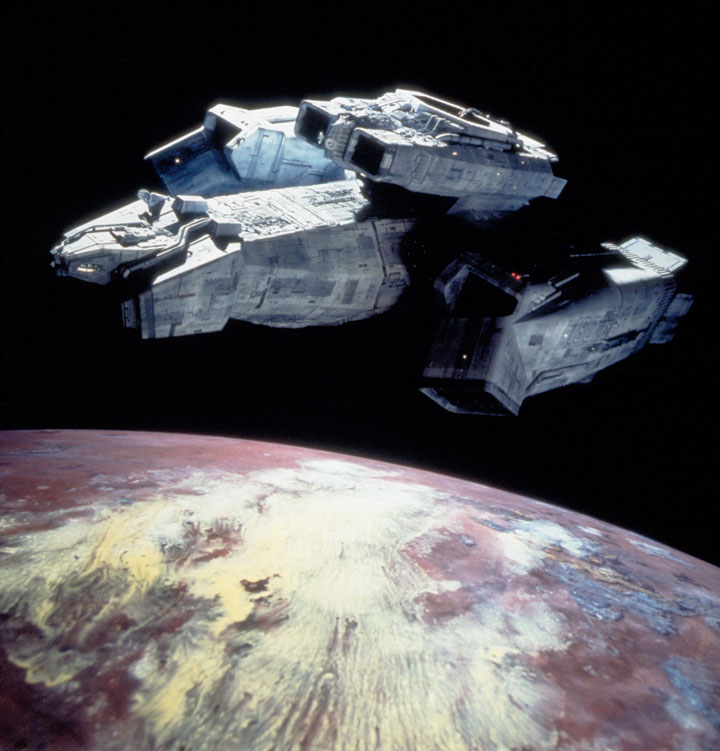

This is commercial towing vehicle Nostromo out of the Solomons, registration number 1-8-0-niner-2-4-6-0-niner.

The challenge now? Someone had to build it.

Someones, that is. Brian Johnson assembled a talented design team composed of now-famous effects artists such as Nick Allder, Ron Hone, Simon Deering Jon Sorenson, Martin Bower and Martin Gant. Their work would be done at Bray Studios outside London. The Nostromo began life as a six-inch conceptual model built by Terry Reid. The team used this three-dimensional sample to develop the design with director Ridley Scott. “There’s nothing like handing a director a model for him to play with and twist around,” Johnson recalls. He also remembers making frequent trips from his visual effects headquarters at Bray to the director and production staff at Shepperton as the Nostromo slowly evolved.

Once they had Ridley’s blessing (no easy feat, if you ask them), the bevy of designers at Bray began building the eleven by seven foot model, ironically called a “miniature.”

The Nostromo started as no more than a steel frame that was constructed to provide skeletal support to the massive (estimated at 500 pounds or more) final build. Chunks of solid wood were shaped and mounted on the steel to serve as the vessel’s “musculature.” Once the Nostromo had a sound understructure, Brian Johnson’s team went to work applying the “skin” to the Nostromo’s industrial surface. This group of artisans called themselves “The Widgeteers,” a dedicated team of detail-oriented engineers, applying hundreds of little plastic widgets in a tedious labor of madness and passion.

The Nostromo’s outer surface was brought to life via a method known as “kit-bashing” where the modellers would raid hobby shops for off-the-shelf model kits and then use the parts from those models to create the very functional-looking outer surface of the miniature. In the case of the Nostromo, certain model kits were “bashed” again and again to give the Nostromo life. Parts that were required in high multiples were sometimes obtained in batches from the models’ manufacturers. The most popular models farmed for their parts? A British Matilda tank from World War II, NASA’s space shuttle, and Darth Vader’s TIE-Fighter. The effects team then used chloroform to literally melt the plastic parts so that they could be shaped to the curving surface of the miniature. Once they were shaped, the chloroform would eat away at the thin styrene model parts, thus bonding them to the wooden understructure. With that much surface area and that many parts, one sincerely hopes that the modelers employed OSHA-approved ventilation during the build.

The build process would not be a streamlined one. Ridley Scott, like any mad genius (see Messers: Hitchcock, Kubrick, Cameron), was not a director to remain “hands off” during pre-production. He was constantly tinkering with not just the Nostromo, but all aspects of the film’s design. As tends to be the case in filmmaking, this didn’t sit well with his artisans. In recalling their work at Bray in 1978, they remember the frustration of having to change the physical model so many times even after it had been assembled and painted. In fact, the Nostromo was intended to be yellow to make it truly appear like an industrial space tugboat. This plan lived long enough that production photos exist of a very real and very yellow Nostromo. But, as the reader might agree, the look of this proved odd, somehow minimizing its imposing presence and muting the enormous amount of detail on the ship’s surface. At Ridley’s direction, the Nostromo was repainted a weathered gray, complete with all the grime and dirt that would be collected over decades of space travel.

---

Check out our next installment of this 5 part series!

NOSTROMO: A LEGEND BORN AND BORN AGAIN: Part 2

---

This is commercial towing vehicle Nostromo out of the Solomons, registration number 1-8-0-niner-2-4-6-0-niner.

ALIEN began as a singular vision of screenwriter Dan O’Bannon.

The inspiration, the legend goes, came to him during a bad case of food poisoning. During his gastronomic misery—something that now might now be attributable to the Chrohn’s disease from which he secretly suffered for decades—O’Bannon envisioned an alien creature bursting out from his tortured innards. From that moment forward, the creative spark haunted him like a lucid, waking dream.

O’Bannon had to see it realized.

But he didn’t want to tread the path that had been taken before. With the exception of Kubrick’s 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, science fiction really hadn’t been given a dramatic treatment yet in film. Most of it was like STAR WARS which, while very successful, was the stuff of myth and fantasy to O’Bannon. Not reality.

The inspiration, the legend goes, came to him during a bad case of food poisoning. During his gastronomic misery—something that now might now be attributable to the Chrohn’s disease from which he secretly suffered for decades—O’Bannon envisioned an alien creature bursting out from his tortured innards. From that moment forward, the creative spark haunted him like a lucid, waking dream.

O’Bannon had to see it realized.

But he didn’t want to tread the path that had been taken before. With the exception of Kubrick’s 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, science fiction really hadn’t been given a dramatic treatment yet in film. Most of it was like STAR WARS which, while very successful, was the stuff of myth and fantasy to O’Bannon. Not reality.

Instead, he wanted to create a very specific science fiction world. Something that felt lived in. Something inherently real. From the characters to the places they lived and worked to the language they used, O’Bannon saw a fully realized future world that was an extrapolation of our own present. One that drew upon the same apprehensions and issues with which he was faced. To make this happen, O’Bannon and producing partner Ron Schuset began assembling what O’Bannon called his “dream team” of designers and artists: Ron Cobb, Chris Foss, Moebius (Jean Giraud) and the now-legendary H.R. Giger.

The dream team set out to breathe reality into O’Bannon’s science fiction world for their new boss, a popular British commercial director named Ridley Scott.

One of the most important pieces of the ALIEN puzzle was the commercial towing vehicle Nostromo, registration number 1-8-0-niner-2-4-6-0-niner. Because, other than a short detour to the planet Acheron (re-dubbed LV-426 by the sequel’s director James Cameron), the whole of the action in ALIEN took place on that fated towing vessel.

The Nostromo, Italian for “mate” or “boatswain,” derives its namesake from the titular anti-hero from Joseph Conrad’s 1904 novel of the same name, a source of great inspiration to O’Bannon. In fact, the fictional mining town where much of Conrad’s novel takes place lends its name to another famed space vessel in the ALIEN universe. That town’s name? Sulaco.

The Nostromo spacecraft was conceived in the vivid minds of Ron Cobb and Chris Foss, both of them already famed conceptual artists when they began work on the film. Cobb came from an industrial background, referring to himself as a “frustrated engineer,” whereas Foss was more “Giger-esque” in his approach to design, dreaming up a spacecraft that felt more other-worldly, or even alien in their aesthetic. The two sequestered themselves away for months to work on creating the Nostromo from scratch. Cobb was meant to tackle the interiors—seen as a much more engineering-like task—while Foss was intended to divine the ship’s exterior. However, the two found that their individual creative processes were not mating up. Cobb’s designs began with function and found their way to form whereas Foss’s approach was the opposite. That’s probably why, after months of work and dozens of conceptual sketches, it was Ron Cobb’s extremely engineer-like design that landed on the desk of visual effects supervisor Brian Johnson.

The dream team set out to breathe reality into O’Bannon’s science fiction world for their new boss, a popular British commercial director named Ridley Scott.

One of the most important pieces of the ALIEN puzzle was the commercial towing vehicle Nostromo, registration number 1-8-0-niner-2-4-6-0-niner. Because, other than a short detour to the planet Acheron (re-dubbed LV-426 by the sequel’s director James Cameron), the whole of the action in ALIEN took place on that fated towing vessel.

The Nostromo, Italian for “mate” or “boatswain,” derives its namesake from the titular anti-hero from Joseph Conrad’s 1904 novel of the same name, a source of great inspiration to O’Bannon. In fact, the fictional mining town where much of Conrad’s novel takes place lends its name to another famed space vessel in the ALIEN universe. That town’s name? Sulaco.

The Nostromo spacecraft was conceived in the vivid minds of Ron Cobb and Chris Foss, both of them already famed conceptual artists when they began work on the film. Cobb came from an industrial background, referring to himself as a “frustrated engineer,” whereas Foss was more “Giger-esque” in his approach to design, dreaming up a spacecraft that felt more other-worldly, or even alien in their aesthetic. The two sequestered themselves away for months to work on creating the Nostromo from scratch. Cobb was meant to tackle the interiors—seen as a much more engineering-like task—while Foss was intended to divine the ship’s exterior. However, the two found that their individual creative processes were not mating up. Cobb’s designs began with function and found their way to form whereas Foss’s approach was the opposite. That’s probably why, after months of work and dozens of conceptual sketches, it was Ron Cobb’s extremely engineer-like design that landed on the desk of visual effects supervisor Brian Johnson.

The challenge now? Someone had to build it.

Someones, that is. Brian Johnson assembled a talented design team composed of now-famous effects artists such as Nick Allder, Ron Hone, Simon Deering Jon Sorenson, Martin Bower and Martin Gant. Their work would be done at Bray Studios outside London. The Nostromo began life as a six-inch conceptual model built by Terry Reid. The team used this three-dimensional sample to develop the design with director Ridley Scott. “There’s nothing like handing a director a model for him to play with and twist around,” Johnson recalls. He also remembers making frequent trips from his visual effects headquarters at Bray to the director and production staff at Shepperton as the Nostromo slowly evolved.

Once they had Ridley’s blessing (no easy feat, if you ask them), the bevy of designers at Bray began building the eleven by seven foot model, ironically called a “miniature.”

The Nostromo started as no more than a steel frame that was constructed to provide skeletal support to the massive (estimated at 500 pounds or more) final build. Chunks of solid wood were shaped and mounted on the steel to serve as the vessel’s “musculature.” Once the Nostromo had a sound understructure, Brian Johnson’s team went to work applying the “skin” to the Nostromo’s industrial surface. This group of artisans called themselves “The Widgeteers,” a dedicated team of detail-oriented engineers, applying hundreds of little plastic widgets in a tedious labor of madness and passion.

The Nostromo’s outer surface was brought to life via a method known as “kit-bashing” where the modellers would raid hobby shops for off-the-shelf model kits and then use the parts from those models to create the very functional-looking outer surface of the miniature. In the case of the Nostromo, certain model kits were “bashed” again and again to give the Nostromo life. Parts that were required in high multiples were sometimes obtained in batches from the models’ manufacturers. The most popular models farmed for their parts? A British Matilda tank from World War II, NASA’s space shuttle, and Darth Vader’s TIE-Fighter. The effects team then used chloroform to literally melt the plastic parts so that they could be shaped to the curving surface of the miniature. Once they were shaped, the chloroform would eat away at the thin styrene model parts, thus bonding them to the wooden understructure. With that much surface area and that many parts, one sincerely hopes that the modelers employed OSHA-approved ventilation during the build.

The build process would not be a streamlined one. Ridley Scott, like any mad genius (see Messers: Hitchcock, Kubrick, Cameron), was not a director to remain “hands off” during pre-production. He was constantly tinkering with not just the Nostromo, but all aspects of the film’s design. As tends to be the case in filmmaking, this didn’t sit well with his artisans. In recalling their work at Bray in 1978, they remember the frustration of having to change the physical model so many times even after it had been assembled and painted. In fact, the Nostromo was intended to be yellow to make it truly appear like an industrial space tugboat. This plan lived long enough that production photos exist of a very real and very yellow Nostromo. But, as the reader might agree, the look of this proved odd, somehow minimizing its imposing presence and muting the enormous amount of detail on the ship’s surface. At Ridley’s direction, the Nostromo was repainted a weathered gray, complete with all the grime and dirt that would be collected over decades of space travel.

---

Check out our next installment of this 5 part series!

NOSTROMO: A LEGEND BORN AND BORN AGAIN: Part 2

Last edited by a moderator: